Travelling north to Seattle feels like going on retreat.

The last few days have been extraordinary. My colleague John Wyver and I have met more than sixty young artists during whirlwind casting sessions in New York and Los Angeles. We've been trying to find two artists with sufficient bravura and artistic merit to feature in a forthcoming television series called Art Race. The premise of the show is simple: is it possible to cross the USA on a single dollar, surviving only on art? We think we've cast the right artists -- but that's another blog.

The last few days have been extraordinary. My colleague John Wyver and I have met more than sixty young artists during whirlwind casting sessions in New York and Los Angeles. We've been trying to find two artists with sufficient bravura and artistic merit to feature in a forthcoming television series called Art Race. The premise of the show is simple: is it possible to cross the USA on a single dollar, surviving only on art? We think we've cast the right artists -- but that's another blog.The two-and-a-half hour flight from Los Angeles passes smoothly and I arrive late at night in a rather shabby, smelly mid-town hotel. The establishment's only mitigating comfort (apart from my room's bed) is the wonderful view it affords of Rem Koolhaas's neighbouring Public Library.

I'm in Seattle, Washington to film the final building of the Christianity film, the Chapel of St.Ignatius on the Seattle University campus. Designed by local wonder-architect Steven Holl, the building is acclaimed as an incredible exercise in shade and light or as Holl describes it, "seven bottles of light in a stone box". Sniffily, I begin to wonder whether his claim might only be empty "architecture-speak"

I'm in Seattle, Washington to film the final building of the Christianity film, the Chapel of St.Ignatius on the Seattle University campus. Designed by local wonder-architect Steven Holl, the building is acclaimed as an incredible exercise in shade and light or as Holl describes it, "seven bottles of light in a stone box". Sniffily, I begin to wonder whether his claim might only be empty "architecture-speak"Early next morning, cameraman Kevin and sound-man Tom have their own reservations. "Doesn't look all that from the outside," they offer helpfully. Maybe, maybe not, but blue skies are forecast and soon we'll have the opportunity of seeing the building in optimum conditions. We've given ourselves only a single day to capture everything we'll need and, with a couple of masses and a wedding to negotiate, the next few hours promise to be fairly full.

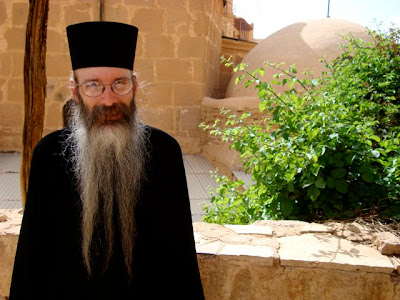

At hand to illuminate us is Father Cobb. A professor at the university, Father Cobb worked with Holl from the building's conception, and proves one of the most effective communicators of the entire series. He has an incredible knowledge -- and passion -- for the building. We're in good hands.

Father Cobb explains the building's genesis (from a water-colour by Holl) and then lays out the broad brush-strokes of the building's design -- the basic procession from grassy lawn to reflecting pool and on to the chapel itself. This is a natural flow which embraces the campus while simultaneously preparing the Catholic congregation for worship.

Father Cobb explains the building's genesis (from a water-colour by Holl) and then lays out the broad brush-strokes of the building's design -- the basic procession from grassy lawn to reflecting pool and on to the chapel itself. This is a natural flow which embraces the campus while simultaneously preparing the Catholic congregation for worship.We learn too about the building's remarkable construction; how twenty-one separate wall-panels were set and then raised into place as interlocking tablets, all in a single day. And we the chapel doors made from Alaskan cedar; Holl has a remarkable skill at designing large heavy-looking doors which are in fact light as a feather to push open. These are beautiful, hand-carved creations.

It's not until we enter the building that the building's true beauty is revealed. Time magazine described Holl recently as "the best architect working in America" and the accolade appears justified when one has the time to spend in any of his interiors. I should confess to being an enormous Holl fan -- during two series of Artland, our recent cultural road-trip through America, we visited several of Holl's creations including the fabulous Bloch Building at the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas. Each one has surprised me with its tireless invention and sense of play.

It's not until we enter the building that the building's true beauty is revealed. Time magazine described Holl recently as "the best architect working in America" and the accolade appears justified when one has the time to spend in any of his interiors. I should confess to being an enormous Holl fan -- during two series of Artland, our recent cultural road-trip through America, we visited several of Holl's creations including the fabulous Bloch Building at the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas. Each one has surprised me with its tireless invention and sense of play. Evident in the St. Ignatius chapel are the seven "bottles of light" which Holl writes about: pools of light refracted through coloured windows, a sort of re-imagining of more classical stained-glass. And consistent with the Bloch Building, it appears impossible to count the interior surfaces -- there are no two alike in the entire space.

Evident in the St. Ignatius chapel are the seven "bottles of light" which Holl writes about: pools of light refracted through coloured windows, a sort of re-imagining of more classical stained-glass. And consistent with the Bloch Building, it appears impossible to count the interior surfaces -- there are no two alike in the entire space.Father Cobb talks us through the stunning font, the confessional space and explains in detail about the way the light changes in the building. More than ten years on from the chapel's inauguration, he says that he's still surprised at how the building changes throughout the day, and indeed from day to day.

The afternoon comes and we have a wedding to film. The bride and groom have kindly allowed us to film during the ceremony and the run-up to the service too. I'm rather fascinated to see that this side of the Atlantic the wedding photos take place before the ceremony. I also can't help thinking that the wedding guests must believe we're the scruffiest, laziest wedding videographers they've ever seen (particularly as we have to wrap before the exchange of vows).

The afternoon comes and we have a wedding to film. The bride and groom have kindly allowed us to film during the ceremony and the run-up to the service too. I'm rather fascinated to see that this side of the Atlantic the wedding photos take place before the ceremony. I also can't help thinking that the wedding guests must believe we're the scruffiest, laziest wedding videographers they've ever seen (particularly as we have to wrap before the exchange of vows). Finally, there's just the opportunity to sneak round the university's art collection. Father Cobb curates the acquisitions and has built up a modest, but impeccably chosen array which is presented to be as accessible as possible for the students. I leave campus with two lovely memories; firstly, the interior of the St. Ignatius chapel, and secondly a student in the campus canteen, tucking into his lunch, perhaps regardless of the priceless Chuck Close portrait just above him. (Seb Grant)

Finally, there's just the opportunity to sneak round the university's art collection. Father Cobb curates the acquisitions and has built up a modest, but impeccably chosen array which is presented to be as accessible as possible for the students. I leave campus with two lovely memories; firstly, the interior of the St. Ignatius chapel, and secondly a student in the campus canteen, tucking into his lunch, perhaps regardless of the priceless Chuck Close portrait just above him. (Seb Grant)